Jackson was born in Cleveland on Oct. 18, 1924, to parents Arthur and Zara Jackson. Soon after his birth, they moved to Canton, Ohio, where he grew up.

In a Library of Congress interview, Jackson said his father was a watchmaker, and he struggled to make money for the family. So, as a boy, Jackson was always trying to help make ends meet by doing odd jobs, such as cutting grass or washing windows. He liked to play baseball and football and was a bugler in the Boy Scouts.

Jackson’s parents moved him to Seattle in 1939, then to Portland, Oregon, a year later, where he graduated from Grant High School. Soon after, he moved to Alaska to work for a naval construction company. While there, Jackson said he met several Marines, which led to his interest in joining, especially because he knew he would likely be drafted into the war anyway.

When Jackson returned to Portland in late 1942, he said he applied to naval flight training, but he didn’t pass the test or the physical. Instead, in January 1943, he enlisted in the Marines.

After training, Jackson was shipped to the Pacific theater. At some point in his first few months of deployment, he received a commendation for saving a wounded Marine.

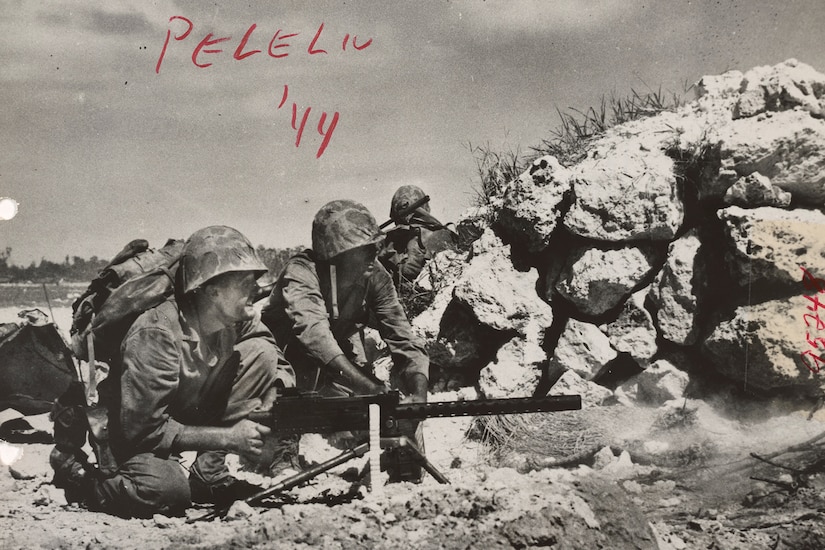

A One-Man Show on Peleliu

By Sept. 15, 1944, Jackson was a private first class serving as an automatic rifleman with the 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines Regiment, 1st Marine Division, which was taking part in the Battle of Peleliu. Peleliu was an island in the Palau Island chains, and it was a steppingstone for the Allies to retake the Philippines.

The battle ended up being much more grueling than Allied commanders thought, taking about two months to complete instead of just a few days.

“When we hit the beach, we landed in about 7 feet of water,” Jackson remembered in his Library of Congress interview. “Once I started getting about knee deep in the water, I looked down that beach in both directions, and it was on fire.”

He said he eventually made it out of the water and ran so fast that he ended up in a staging area with a different regiment before getting back on track and joining elements of his regiment by the island’s air strip. Their mission was to clear the enemy from the southern end of the island.

On Sept. 18, Jackson said they were on a fishhook-like peninsula and pinned down by fire when his superiors asked him if he could get to a particular trench line. They said if he could do it, he could eliminate the enemy bunkers that were pinning them down.

Jackson replied with what any private first class would likely say – that he would try. So, he loaded himself up with grenades and ammunition for his rifle, then took off. Jackson said many of his comrades were hit by fire as he ran, but he wasn’t.

“I was just unbelievably lucky that day,” Jackson said.

As he reached one enemy bunker, he heard the enemy talking, so he tossed a phosphorous grenade inside.

“The smoke just poured out of that bunker entrance,” he said. “That gave me lots of cover.”

Jackson continued to defy heavy enemy barrages, charging a large pillbox that had about 35 enemy soldiers inside. He poured automatic fire into the opening of the bunker to trap the occupying troops. When Jackson realized he would need help eliminating them, his squad leader made his way forward with a load of plastic explosives.

Jackson said he stuffed about 40 pounds of explosives into the opening in the bunker.

“I had about a 30-second time fuse — just a small piece of time fuse — and a striker. I just set that thing on fire, and then I took off running,” Jackson remembered. “And just about the time I dove into a [bomb crater] and covered myself up in the fetal position, logs, stones, earth — honest to God, it was an unbelievable amount of stuff that went up 40, 50, 60 foot.”

“I thought, ‘Boy, I’m going to be done in by my own stupidity,'” he continued. “But when the dust all settled, there was no more bunker.”

All of the enemy soldiers inside had died. Jackson shook himself off and continued to advance alone, employing similar tactics on other smaller hostile emplacements. He was determined to crush the entire pocket of resistance despite the intense enemy fire.

“I still had ammo left, and I just figured I’d better get to as many of these [bunkers] as I can,” he said.

According to his Medal of Honor citation, “he stormed one gun position after another, dealing death and destruction to the savagely fighting enemy in his inexorable drive against the remaining defenses.”

“To this day, I don’t understand why they didn’t vacate some of those positions and come after me,” Jackson recalled. “They must have thought I was more than one person doing this.”

In total, officials said Jackson succeeded in wiping out 12 pillboxes and 50 Japanese soldiers. His one-man assault was a major contribution to the complete annihilation of the enemy in the southern sector of the island.

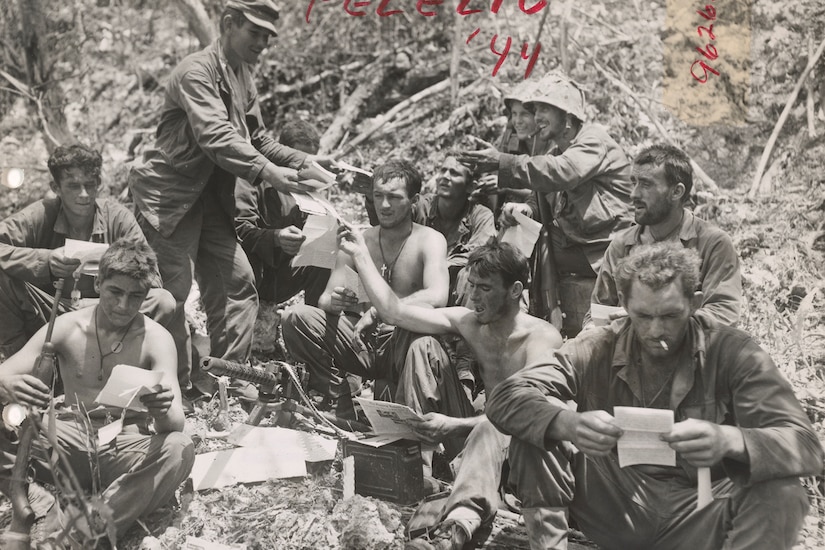

Jackson said he eventually passed out from heat exhaustion, then woke up to his fellow Marines congratulating him. The fighting continued though, and at some point, he was shot in the neck and had to be evacuated off the island. A doctor told him that the bullet they found was about a millimeter from his jugular vein.

“He said, ‘If you had rolled over or turned your head in the wrong way, you’d be a dead man,'” Jackson remembered.

New Assignments & Honors

Jackson eventually recovered and returned to his regiment. In the spring of 1945, he’d moved up to platoon sergeant in time to land on the shores of Okinawa as that campaign began.

By late May 1945, Jackson was preparing to be sent back to the U.S. to go to officer candidate school. However, he injured his knee just beforehand, so he had to stay behind and get treatment in a hospital in Hawaii, where he said he contracted malaria and pneumonia.

Once he finally got better, Jackson said he learned he would be earning a field commission instead of going to officer candidate school. So, in August 1945, he was commissioned in Hawaii as a second lieutenant. Jackson was then sent to a Marine barracks in Oregon to be monitored by malaria researchers who had set up there.

After about a month, he was sent home. That’s when Jackson said he got a wire inviting him to Washington, D.C., to receive the Medal of Honor.

Jackson and his family drove from Oregon to the capital, where he received the nation’s highest honor for valor from President Harry S. Truman on Oct. 5, 1945. Thirteen other Medal of Honor recipients also received the award that day.

Jackson said he was also able to participate in ticker-tape parades in D.C. and New York, which were attended by other famous names such as Adm. Chester Nimitz, Marine Corps Col. Gregory “Pappy” Boyington and newsman Walter Winchell.

“We had one hell of a time,” Jackson said of the celebrations. “That was the highlight of my dad’s life.”

However, while he was being celebrated, Jackson said he never thought himself a hero.

“No,” he said when asked. “I was just a damned good AR-man who had a lucky day.”

From the Marines to the Army

Jackson eventually gave up his commission, taking instead the enlisted rank of master sergeant so he could serve in China during the post-war occupation. When he came back to the U.S., he briefly returned to civilian life but quickly decided to join the Army Reserve. He served on active-duty during the Korean War and eventually earned his Army commission, attaining the rank of captain by 1954. However, Jackson transferred back to his Marine Corps roots in 1959.